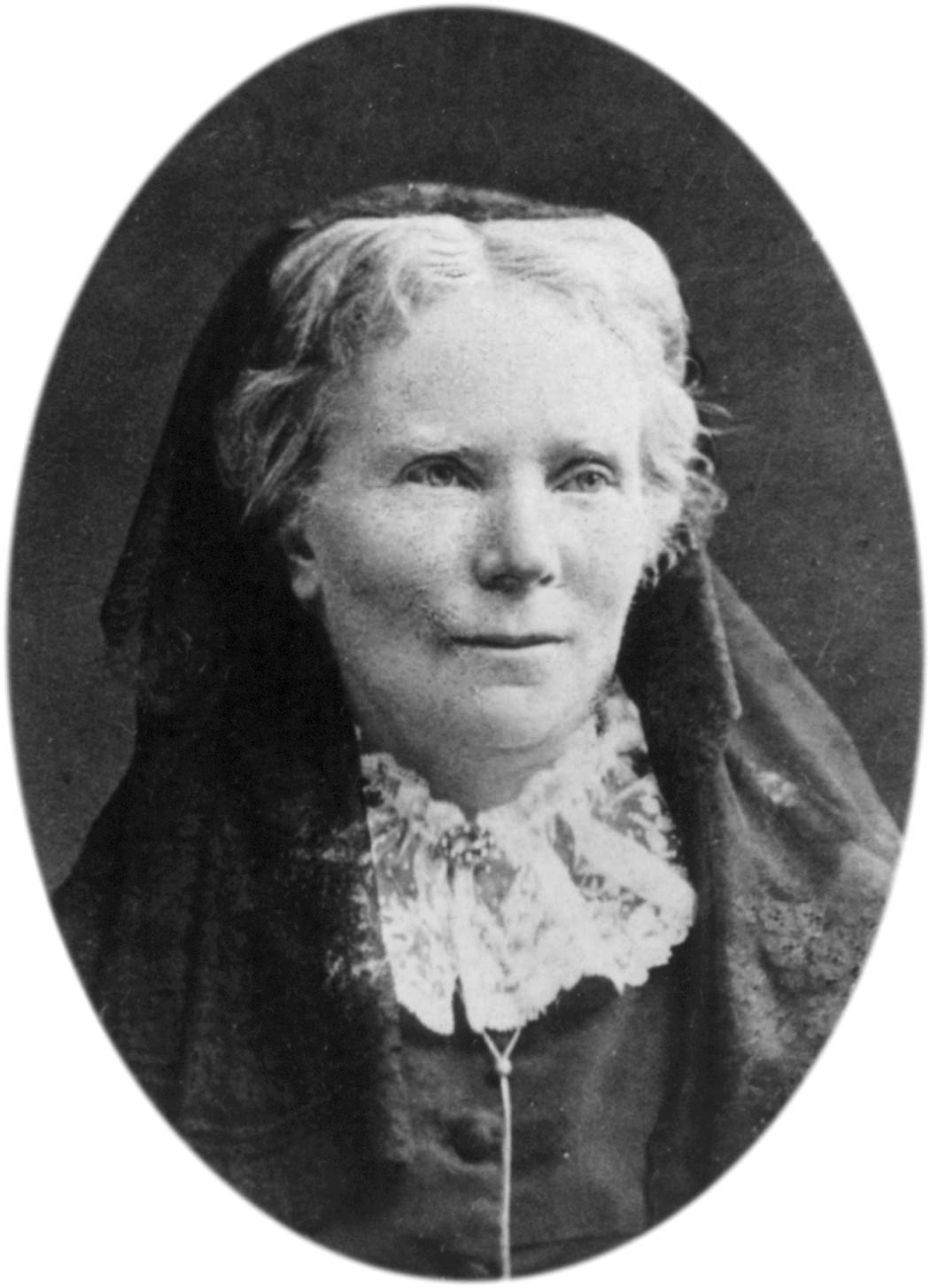

ELIZABETH BLACKWELL

Source WomensHistory.Org

The first woman in America to receive a medical degree, Elizabeth Blackwell championed the participation of women in the medical profession and ultimately opened her own medical college for women.

Born near Bristol, England on Feb. 3, 1821, Blackwell was the third of nine children of Hannah Lane and Samuel Blackwell, a sugar refiner, Quaker, and anti-slavery activist. Elizabeth’s famous relatives included her brother Henry, a well-known abolitionist and women’s suffrage supporter who married women’s rights activist Lucy Stone; Emily, who followed her sister into medicine; and sister-in-law Antoinette Brown Blackwell, the first ordained female minister in a mainstream Protestant denomination.

In 1832, the Blackwell family moved to America, settling in Cincinnati, Ohio. In 1838, Samuel Blackwell died, leaving the family penniless during a national financial crisis. Elizabeth, her mother, and two older sisters worked in the predominantly female profession of teaching.

Blackwell was inspired to pursue medicine by a dying friend who said her ordeal would have been better had she had a female physician. Most male physicians trained as apprentices to experienced doctors; there were few medical colleges and none that accepted women, though a few women also apprenticed and became unlicensed physicians.

While teaching, Blackwell boarded with the families of two southern physicians who mentored her. In 1847, she returned to Philadelphia, hoping that Quaker friends could assist her entrance into medical school. Rejected everywhere she applied, she was ultimately admitted to Geneva College in rural New York, however, her acceptance letter was intended as a practical joke.

Blackwell faced discrimination and obstacles in college: professors forced her to sit separately at lectures and often excluded her from labs; local townspeople shunned her as a “bad” woman for defying her gender role. Blackwell eventually earned the respect of professors and classmates, graduating first in her class in 1849. She continued her training at London and Paris hospitals, though doctors there relegated her to midwifery or nursing. She began to emphasize preventative care and personal hygiene, recognizing that male doctors often caused epidemics by failing to wash their hands between patients.

In 1851, Dr. Blackwell returned to New York City, where discrimination against female physicians meant few patients and difficulty practicing in hospitals and clinics. With help from Quaker friends, Blackwell opened a small clinic to treat poor women; in 1857, she opened the New York Infirmary for Women and Children with her sister Dr. Emily Blackwell and colleague Dr. Marie Zakrzewska. Its mission included providing positions for women physicians. During the Civil War, the Blackwell sisters trained nurses for Union hospitals.

In 1868, Blackwell opened a medical college in New York City. A year later, she placed her sister in charge and returned permanently to London, where in 1875, she became a professor of gynecology at the New London School of Medicine for Women. She also helped found the National Health Society and published several books, including an autobiography, “Pioneer Work in Opening the Medical Profession to Women” (1895).

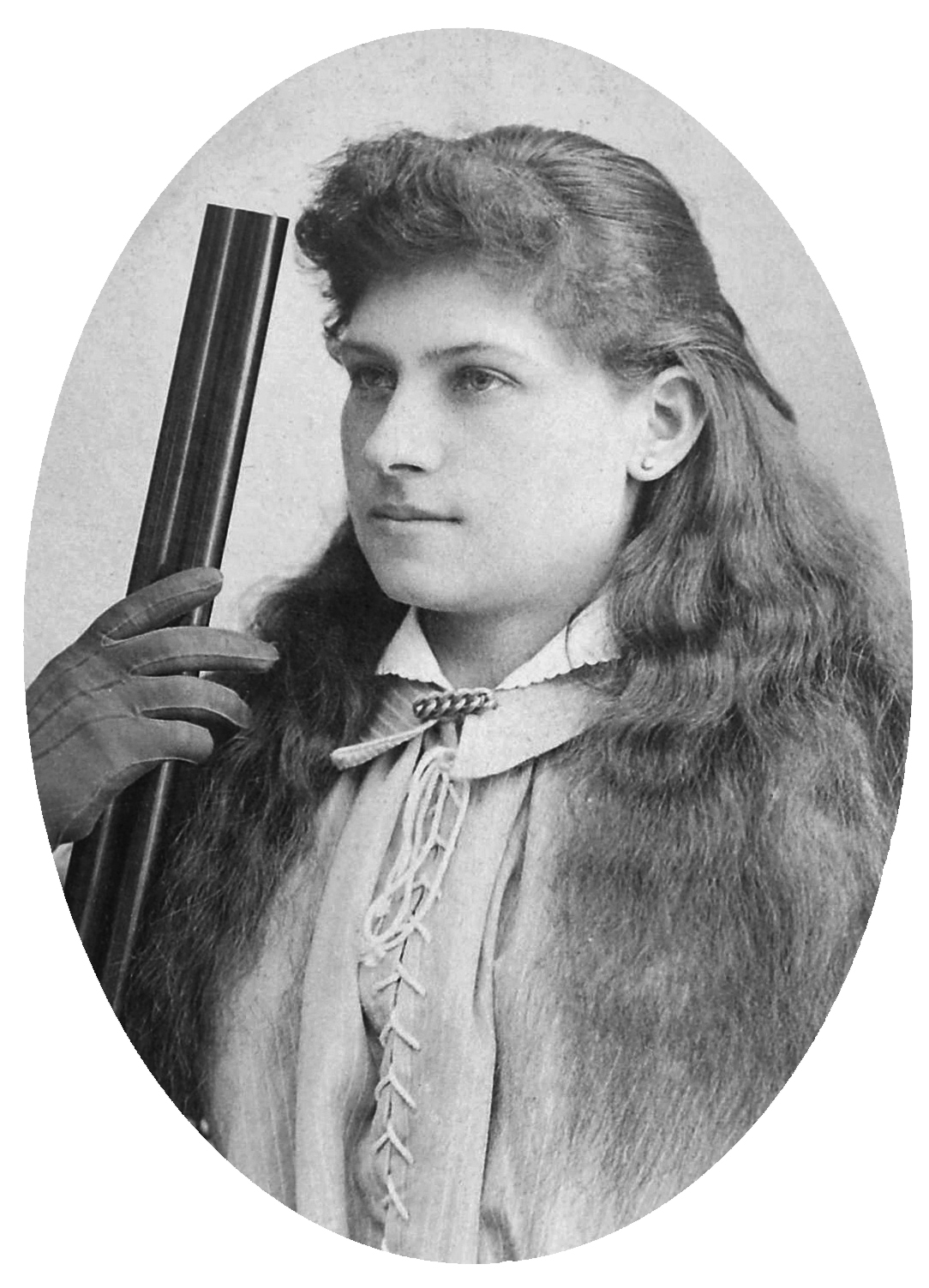

ANNIE OAKLEY

Paula J. Luttrell

American legend, Annie Oakley was a 5-foot-tall master sharpshooter nicknamed “Little Sure Shot” by Chief Sitting Bull, who was so impressed that he “adopted” her and gave her the Native American title “Watanya Cicilla.”

Oakley never failed to delight her audiences and her feats of marks-woman-ship were truly incredible. But her life getting there was far from easy.

Born Phoebe Ann Mosley in 1860, in a log cabin in rural Ohio, she was the sixth of nine children. Her father survived fighting in the war of 1812, but became an invalid after a blizzard caused him to suffer from hypothermia. Because of the poverty the family experienced after his illness and death, Annie did not attend regular school as a child. She and one of her sisters were admitted to the Darke County Infirmary. Annie was put in the care of the infirmary’s superintendent and his wife, who taught her to sew and decorate. She was later “bound out” to a local family to care for their infant son, with the false promise of 50 cents per week and an education. They enslaved her for nearly two years and tortured her, both mentally and physically. Annie finally ran away when she was 12. She referred to the couple as “the wolves” and never revealed their names.

Annie had begun trapping at the age of 7, and hunting and shooting by the age of 8. She sold what she hunted to local shopkeepers and restaurants. Her profits paid off her mother’s small farm by the time she was just 15.

The young girl soon became well known throughout the region.

On Thanksgiving Day 1875, traveling show marksman Frank E. Butler was performing in Cincinnati. Frank placed a $100 bet with a local hotel owner that he could best any fancy shooter in Ohio. The hotelier arranged a match between Butler and Annie. The last thing Frank expected was a 5-foot-tall teenage girl as his opponent. After missing on his 25th shot, Butler lost the match and the bet. A year later, Annie and Frank were married and began performing together.

The couple joined Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show in 1885. The three-year tour cemented Oakley as America’s first female star. She earned more money than anyone else in the show besides Buffalo Bill himself.

Annie performed in other shows for extra income. In Europe, she put on shows for heads of state, like Queen Victoria of the U.K., King Umberto I of Italy, and President Marie Francois Sadi Carnot of France. She shot the ashes off a cigarette help by newly-crowned German Kaiser Wilhelm II at his request.

Oakley promoted the service of women in combat operations for the United States armed forces. She wrote a letter to President William McKinley in 1898, offering the services of 50 “lady sharpshooters,” who would provide their own arms and ammunition should the U.S. go to war with Spain. Her offer was not accepted but Teddy Roosevelt did name his volunteer cavalry the “Rough Riders” after the performers in Buffalo Bill’s show, where Annie was a major star.

Throughout her career, it is believed that Oakley taught more than 15,000 women how to use a firearm. She felt it was crucial for women to know to use a gun, as not only a form of physical and mental exercise, but also as a means to protect themselves. She said, “I would like to see every woman handle guns as naturally as they know how to handle babies.”

Annie Oakley has been well-represented in arts and entertainment. Barbara Stanwick played Oakley in the namesake 1935 film. The 1941 Irving Berlin Broadway musical, “Annie Get Your Gun,” is based on her life, and was reprised in 1966. Ethel Merman starred in both productions. A 1950 film version of the musical starred Betty Hutton and Howard Keel. Several years after headlining the 1948 national tour, Broadway legend Mary Martin returned to the role for a 1957 NBC television special. Oakley also had a television series named after her, and has been portrayed in many movies including “Tall Tales and Legends,” “Buffalo Girls,” and “Hidalgo.”

Over the course of her career, Annie Oakley showed people around the world that women were capable and able to handle firearms and even out-shoot men. She encouraged women to master the use of pistols they could keep in their purse to protect themselves. She was passionate about empowering women and protecting children.