I’m a Black man, lifelong San Diegan and a member of the LGBTQ+ community. I’ve worked in the insurance industry for over 23 years and for the last several years, I’ve volunteered for nonprofit organizations. I’m a member of Mayor Kevin Falconer’s Advisory Board as well as the San Diego County Sheriffs Advisory Board. My proudest achievement is being the founder/director of Take What You Need, which is a weekly free food distribution program. This is my story about my attendance at last week’s March on Washington, which was 57 years in the making.

In the first quarter of 2020, the devastating effects of the coronavirus started to become clearer. Millions of people lost their jobs and many more were forced to remain at home due to statewide mandates. The continued isolation and uncertainty had an adverse effect on many people. The gravity of our new normal seemingly reached a breaking point on May 25, 2020, when a white police officer, knelt on the neck of a handcuffed Black man for 8 minutes and 47 seconds. George Floyd’s murder was recorded by onlookers as they pleaded with officers to help him, but their pleas were ignored.

Although George Floyd was not the first unarmed Black man to be killed by the negligence of a law enforcement officer, this time was different. The event occurred in broad daylight after Floyd was accused of passing a counterfeit $20 bill; he was unarmed and on his stomach with three officers holding him down. We could see his face clearly in high definition as he narrated his own death and pleaded with the officers by repeating the words, “I can’t breathe.” At one point, the 46-year-old Floyd called out for his deceased mother before losing consciousness and upon taking his last breath, urinated on himself.

This horrific incident transcended race, age, socioeconomic class and most notably, politics. Although America was enduring the ravages of COVID-19, millions took to the streets to march against police brutality. “Black Lives Matter” became the nation’s rallying cry and no matter one’s gender identity, age, generation or race, unity seemed possible — but like many high-profile incidents, unity was short lived. Some citizens took the opportunity to steal, destroy and deface property. Although the families of recently killed Black men have publically denounced this behavior, some in media and politics have decided such action can be used to their advantage during an election year.

On Tuesday, June 9, 2020, George Floyd was laid to rest. The eulogy was given by Rev. Al Sharpton, and as I watched it live from my living room, I cried. The words spoken by the reverend were compelling. During the eulogy, he talked about the 1963 March on Washington and the parallels that exist today. He announced that on the 57th anniversary, he and Martin Luther King III are going back to march one more time. I was so inspired I booked my flight before he finished his speech.

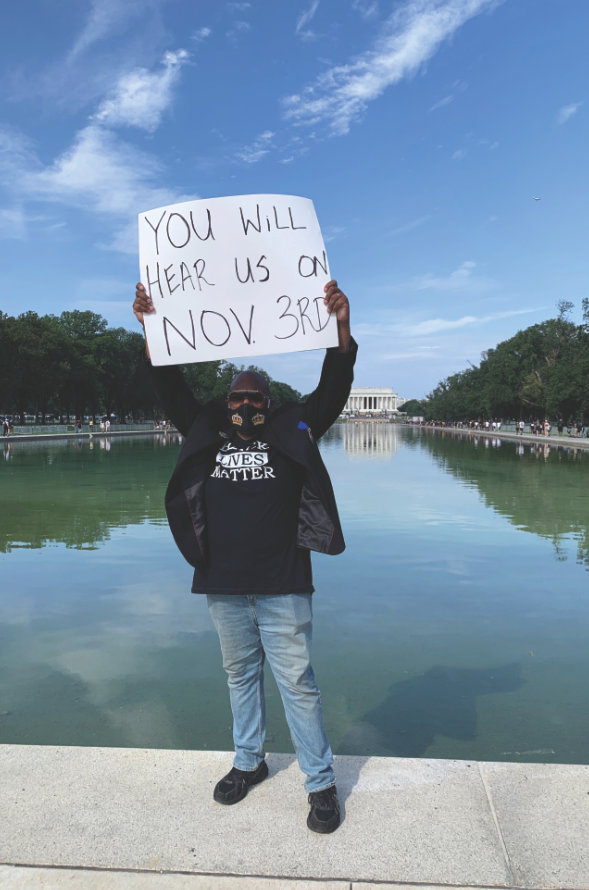

The march took place on Friday, Aug. 28, 2020 — exactly 57 years after the infamous 1963 March on Washington. Black was the primary race of the attendees, but the crowd was definitely mixed with representation from every ethnic background, which was a welcome contrast to the photos I’ve seen from the first march in 1963. Wearing a black sports coat, jeans and a face mask, I arrived around 9:30 a.m., stood in line for a temperature check and was given an additional mask, sanitizer, gloves and offered a complimentary rapid COVID-19 test. Wearing a mask in 92-degree heat with 53% humidity made it difficult to breathe, but seeing my elders endure these conditions made me tough it out. The National Mall was filled with cases of complimentary water and sports drinks as vendors were not permitted. As I walked along the Reflecting Pool toward the Lincoln Memorial, I could hear individuals speaking and I settled on the steps directly in the center facing Lincoln’s statue. I could see the speakers on the giant screens provided and there were several notable speeches that I found to be inspiring.

Alaya Eastman spoke, she currently attends Trinity Washington University but she spoke as a survivor of gun violence that she witnessed while she was a student at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida. She spoke about lying beneath the lifeless body of a classmate in order to survive and emphasized the pervasive gun violence that plagues poor Black communities. Eastman mentioned that the flow of guns into struggling communities is a direct result of poor choices and policies set forth by lawmakers and are often accompanied with racial undertones. She went onto to say gun violence in poor Black communities is not inherent or a coincidence, it’s by design.

Next, was the first Black woman elected to Congress from the commonwealth of Massachusetts, Congresswoman Iona Pressley. She spoke of our Black ancestors, not the ones in the history books but the everyday heroes in our very own communities and how each and every single one of us are examples of social and political progress in this country, but we still have a ways to go.

The most powerful speech of the day was given by Doctor Jamal Harrison Bryant. He began by speaking softly and mentioned a powerful quote from Harriet Tubman who said, “I freed thousands of slaves, and I would have freed hundreds more; had they known they were slaves.” The paralysis of fear was a running theme throughout his speech. He spoke about not being paralyzed when it comes to voting this November because of Kamala’s past as a prosecutor without thinking about what she wants to accomplish on behalf of our future — like abolishing privatized prisons, no more mandatory minimum sentences and the legalization of marijuana. He spoke about not being paralyzed when it comes to support of Black Lives Matter because the founders are three lesbians, because members of the LGBTQ+ community are our sons, daughters, brother, sisters, friends and neighbors. He spoke about the recent shooting of Jacob Blake, now paralyzed after being shot seven times in the back by a police officer. With a loud voice he spoke about the resiliency of Black people stating, “If we are rendered paralyzed, we’re gonna crawl to the polls! You take away the mailboxes, we’re still gonna crawl! You take away polling stations, we’re still gonna crawl! Like a butterfly, we’ve got two options, we’re gonna crawl or we’re gonna fly!”

And lastly, Rev. Al Sharpton gave a moving and inspirational address to the 150,000-plus attendees. He began by speaking about the men and women who attended in 1963 and said, “Many of them couldn’t stop along the road to use the restroom because it was against the law, but they came anyhow. Many of them couldn’t stop to eat at a restaurant, because no restaurant would serve them; because it was against the law, but they came anyhow. Many of them couldn’t rest in a hotel overnight but they came anyhow.” He went on to say because they came in ’63, we are able to be here in 2020 by any means of our choice, staying at any hotel and eating anywhere we want to eat. At one point, I began to cry and put my glasses on because of the dozens of news outlets and photographers looking for a memorable shot. He spoke about how coming together is not enough, saying “demonstration without legislation will not lead to change.” The reverend wants three things to occur as a result of this rally: an end to police brutality, passage of the George Floyd Policing and Justice Act, and the passage of the John Lewis Voting Rights Act. Rev. Sharpton’s speech was motivating and galvanized the audience.

There were additional speeches from individuals from around the country including Martin Luther King III, Congresswoman Sheila Jackson Lee, Democratic National Committee Head Tom Perez along with family members of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Jacob Blake and many more — including a pre-taped message from Senator Kamala Harris. It was a pleasant surprise that so many speakers mentioned Bayard Rustin, an openly Gay Black man who organized the first March on Washington more than 57 years ago.

As I sit here, I am still digesting the magnitude of this event but I do realize if the people who attended (myself included) don’t work toward change, the trip was all in vain. The sense of community and caring for one another was on full display. Reading the homemade signs gave me a sense of who the person was and why they were there. The space felt safe, welcoming, and at times spiritual and I believe many left feeling healed. I spoke with an older Black gentleman who said that he prays this is the last time we’ve got to do this, I agreed with him but thought, how do we stop violence from occurring? The following day, I took a picture of a pin worn by attendees on Aug. 29, 1963, and the message was simple: “Jobs & Freedom.” I guess we’re still looking for a little bit of both in 2020.