Resources: sdpride.org, sdpride.sdsu.edu, Lambda Archives, research on the interwebs, Doug Moore Facebook memories, and other first-person personal commentary and memories. For more historical detail about those who made Pride what it is in the early years, visit sdpride.org/history-of-pride.

“A community, indeed a movement, that does not know its history or the shoulders it stands on, does not know where it’s going.”

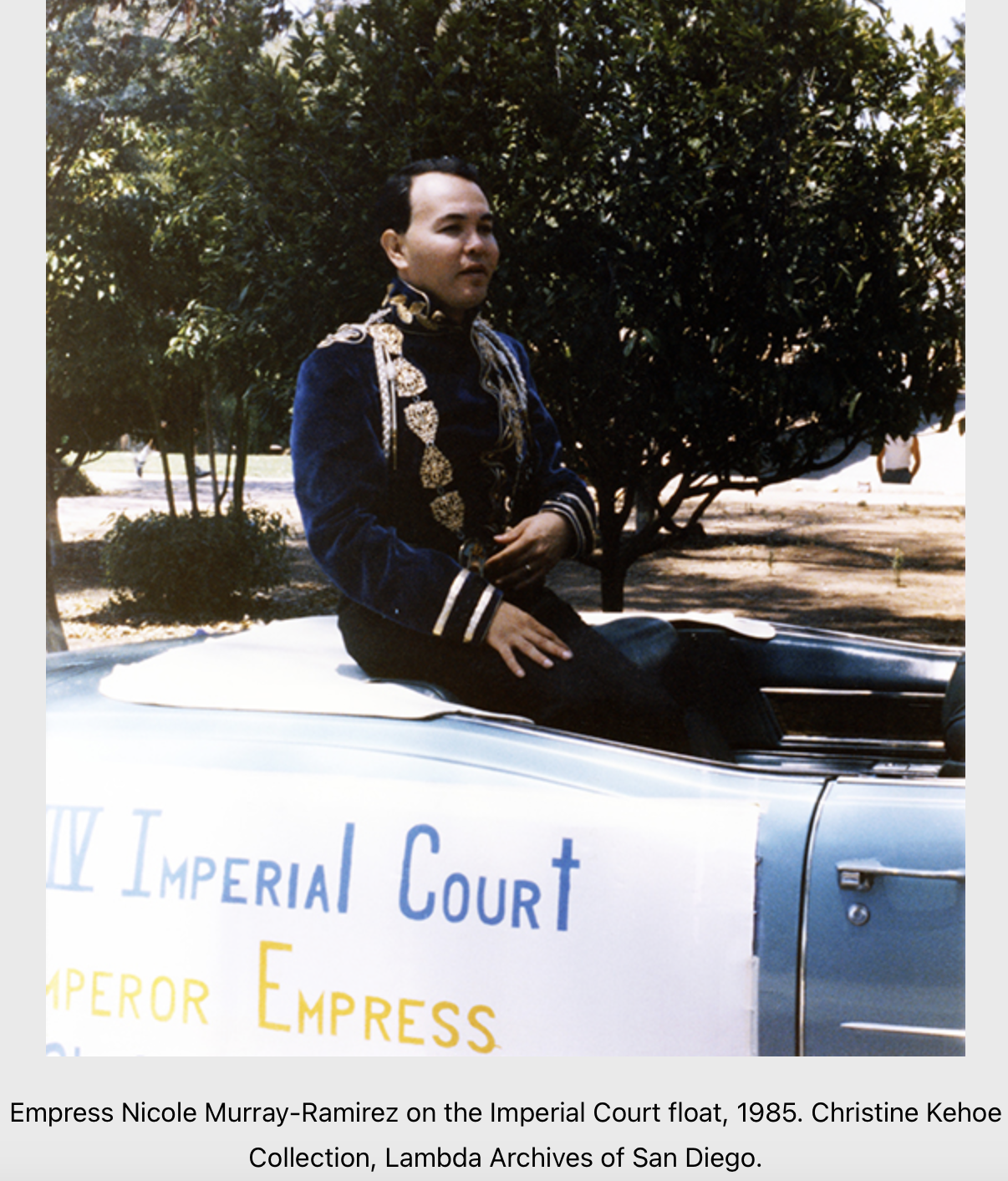

– Nicole Murray Ramirez

“The annual celebration of Pride has marked many of our struggles and accomplishments. Remember that when we started this, we were presumed criminals, given the presence of the laws prohibiting sex between persons of the same sex and the “cross-dressing” laws. Each year reflected those struggles, from the Anita Bryant campaign to the Briggs Initiative, to the assassination of Harvey Milk, to the repeal for DADT, to marriage equality. Every year reflected the struggles and joys of our people.”

–Bridget Wilson

San Diego celebrates its 50th celebration of Pride this year with the first march taking place in 1974. Its roots started a few years earlier, however, in 1970, when students at San Diego State College (now SDSU) founded the San Diego Chapter of the Gay Liberation Front (GLF) in 1970.

These students, including one of the fathers of San Diego’s LGBTQ movement, Jess Jessop, organized a series of early protests and “Gay-Ins,” celebratory picnics held at Presidio Park in San Diego. It soon became clear to local activists that it was time to organize a more coordinated Pride march.

1974

According to Nicole Murray-Ramirez, he, along with Jess Jessop and local ACLU attorney Tom Homann, applied for a permit for the first protest march in 1974, but were denied. Ramirez said they were told, “There will never be a gay march in San Diego.” People gathered for an ad hoc march anyway, many with bags over their heads to hide their identities.

Note: The Pride march that took place the following year may have been organized and permitted – but that permit came after the ACLU threatened to sue the City of San Diego after denying the previous permit.

While many still considered 1975 to be the first Pride march, others felt that to dismiss the march in 1974 would be a disservice to the people who were brave enough to participate.

1975

A committee established the Lesbian/Gay Men’s Pride Alliance and sought permits with the help of volunteer attorneys. Not without struggle, the permits were obtained, marking 1975 as the year of the first permitted march and rally. The march took place from Horton Plaza to Balboa Park. Barbara Gittings was grand marshal. Although government officials were predominantly not yet vocal in their support of gay rights, Councilwoman Maureen O’Connor sent the organizers a message of support the morning of the march.

1976

It was the Bicentennial of the US, so the Pride theme was “Gay Spirit.” Floats and/or vehicles were charged a $5 fee to be in the Pride march.

A permit was obtained (after another initial refusal – and the refusals continued every year for nearly a decade).

1977

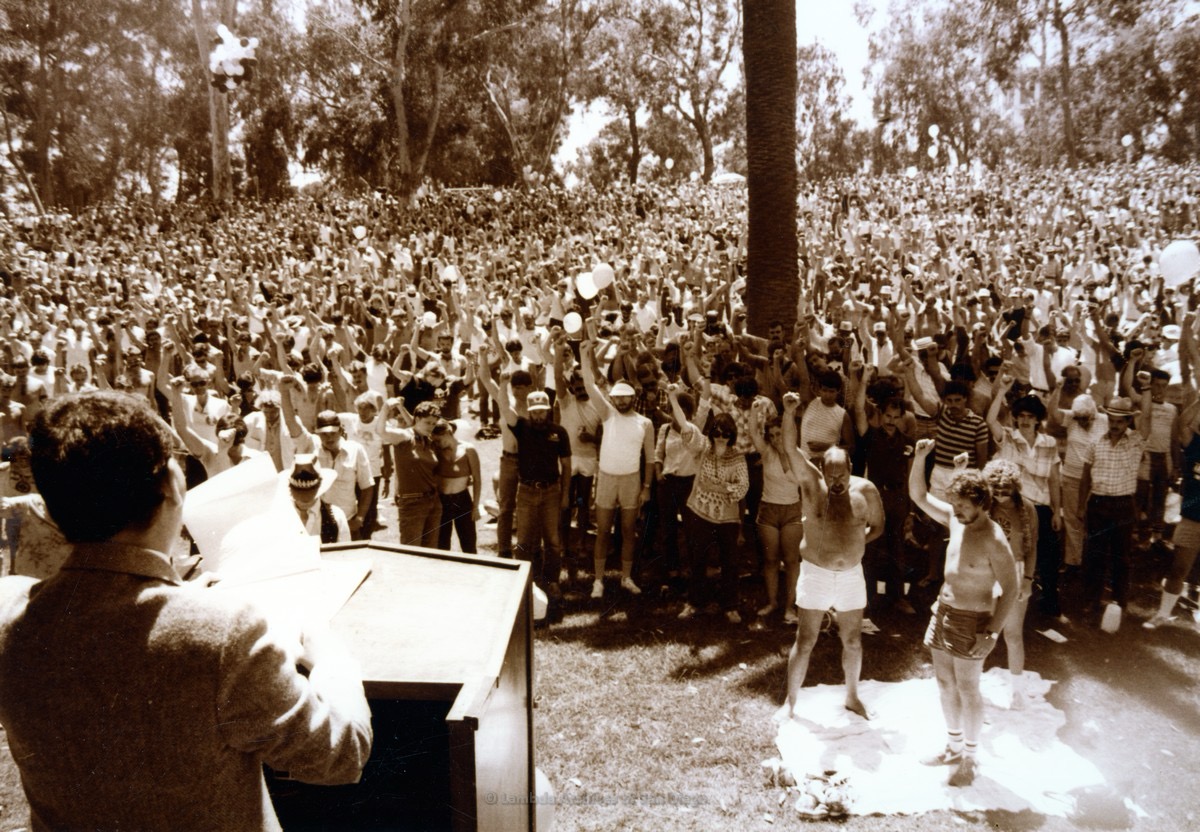

Participation continued to increase. America was in the throes of the Anita Bryant “Save Our Children” crusade, so the theme of the march became “Unity (A Day With Human Rights Is Like A Day Without Sunshine),” which referenced Bryant’s commercial for the Florida Citrus Commission proclaiming that “a breakfast without orange juice is like a day without sunshine.” Over 1,000 people attended the march. Jess Jessop and Gloria Johnson were named grand marshals.

1978

Defending homosexuality in education took the spotlight of the 1978 Pride event, which was held on June 25. California voters faced Proposition 6, a measure that would prohibit gays and lesbians from teaching in public schools and prohibit the use of curricula that presented homosexuality positively. Prop 6 was fueled by Anita Bryant’s anti-gay campaign and sponsored by California State Senator John Briggs. The march and rally saw 1,500 attendees that year, but the mayor of San Diego refused to proclaim a Gay Pride Week.

1979

The march was moved from Sunday to Saturday, June 23. This year, the march proceeded across Balboa Bridge (now known as Cabrillo Bridge) into Balboa Park, to the rally at the Organ Pavilion.

A competing event at Balboa Park that August, the “2nd annual Gay Picnic and Olympics” – which was purposely promoted as a social rather than political event – saw 2,500 attendees, which impacted attendance at the march and rally in June.

1980

Learning a lesson from the impact of the Gay Picnic the year before, organizers decided to create a more “celebratory” tone and changed the march to a parade. This caused many lesbians to break from the planning organization (Lesbian/Gay Men’s Pride Alliance) and start their own focus and march – which later became known as Dyke March – taking place the week prior to the June 21 parade.

1981

In what became known as the first year of the AIDS crisis, the Lesbian/Gay Men’s Pride Alliance disbanded and Doug Moore formed Lambda Pride. They asked Mayor Pete Wilson’s office to proclaim Pride Week but were refused.

The route of the June 13 parade changed; it now started and finished in Balboa Park. The new route started at Sixth Avenue and Laurel Street, traveled up Sixth, turned left onto Thorn Street, right onto Fifth Avenue, right onto Robinson Avenue, and right again back down Sixth Avenue, where it eventually ended up in Balboa Park. This was also the first year of the Pride festival, held on Juniper Street between Fifth and Sixth avenues. The celebration featured food vendors, games, performances, and alcohol, which was given away free since Lambda Pride had not yet acquired a license to sell. The Moral Majority picketed all events and SDPD could not interfere because it was all public property. The parade had 3,000 attendees and many more contingents. Gloria Johnson and Brad Truax were grand marshals.

1982

The parade theme was “Proud Diversified United,” and had 46 contingents. This was the first year since the marches began that there was no rally afterward and all the events had less political themes overall.

The festival moved to private property to avoid the protestors. That property was none other than West Coast Production Company (WCPC) on Hancock Street. WCPC was owned by Chris Shaw, who allowed Lambda Pride to use his liquor permit, but attendees had to go inside to drink. The festival was held in the bar’s dirt parking lot – which became known as the “dustbowl” – and had 30 booths.

1983

Lambda Pride’s nonprofit status became official. Permits for the parade were again denied – but then approved after Tom Homann helped them file an appeal and they contacted the media. It was the first year of the Gay Pride Run. There were 55 contingents, 5,000 spectators, and no rally at the end. The festival was again at WCPC with 40 booths. Robin Tyler, among others, performed.

Significantly, Republican Mayor Roger Hedgecock proclaimed June 11, 1983, as “Human Rights Day” to honor the “economic, cultural and intellectual diversity” and contributions of the gay community.

“We were ecstatic to get it, but disappointed it didn’t say ‘Pride,’” Nicole Murray Ramirez said. Doug Moore read the proclamation to attendees of the festival.

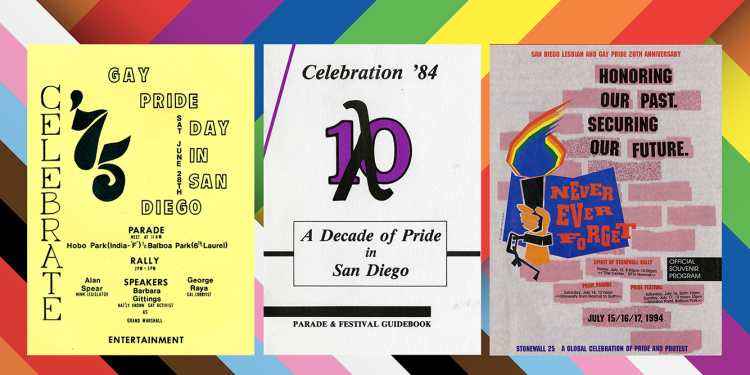

1984

The 10th anniversary’s theme was “Unity and More in ’84,” and it was the first year there were no issues with the permits. The parade started at noon from Sixth Avenue and Laurel Street, with 74 contingents, 1,200 people participating, and between 6,000-10,000 spectators. The rally returned and was well attended. The festival was held Sunday at WCPC with $2 admission, and 4,000 attended.

Christian fundamentalists protested extensively in the weeks leading up to Pride that year. In anticipation of their presence, activist Mary Lou SanBlise and her partner, Sandy, trained 25 people to establish a human “buffer zone” between the parade marchers and the fundies. This group became known as the “Future Former Fundy Fighters.” They wore white T-shirts, lavender sashes, and jeans, and were instructed to smile, laugh, and sing in the presence of fundies. A few hundred protested. Doug Moore left after disagreements with the board.

1985

A new board took over and Doug Moore returned. The theme was “Alive with Pride in ’85,” with the festivities held June 8-9. The biggest change that year was the site of the festival, which moved to the County Administration parking lot along the Embarcadero: no more dust, but all asphalt. There was no alcohol, which proved to be an important option and post-Pride, the board was ousted by the community.

1986

With yet another new board, the budget grew to $90,000 and a two-day festival was planned for the first time; but the new board couldn’t deliver and Pride was initially canceled. On May 19, with Pride weekend just weeks away, an ad-hoc committee was organized to save Pride, which included Lambda Pride veterans Doug Moore, Chris Shaw, Michele Cody, Tom Tyrell, Chris Kehoe and Pat Burke. A public meeting was held at The Flame, and a new Lesbian and Gay Pride Association was formed, with David Manley selected as head coordinator.

Chris Shaw, long time supporter of Pride, wrote a check for $5,000 to the new organization and once again offered the parking lot of WCPC for the festival. They managed to pull off a parade, rally and two-day festival in very little time.

Proposition 64, or the “LaRouche initiative,” was on the ballot, which would have bolstered discrimination on the basis of AIDS. Nicole Murray Ramirez, Robin Tyler, and Susan Jester delivered heated speeches at the rally calling for action. Grand marshals that year were Bridget Wilson and Terry Cunningham. The festival had 6,000 attendees.

1987

“New Lambda Pride” is formed and takes over. Following through on a campaign promise, Mayor Maureen O’Connor participated in the parade with the San Diego AIDS Project, walking alongside the mother of an AIDS patient. O’Connor became “the first elected head of a major US city to walk in sympathy with homosexuals.” She was both cheered and booed during the parade and later received hate mail and death threats. Publicly, she stated that she was not condoning or condemning anyone, just showing support. SDPD escorted the parade with two squad cars and 10 motorcyclists.

A rally followed the parade at Marston Point in Balboa Park, where 8,000 attendees found 289 styrofoam crosses draped in black ribbons and lavender orchids – a cross for every AIDS-related death in San Diego.

Nicole Murray Ramirez, the last speaker at the rally, encouraged attendees to take the crosses to city officials, and thousands of people then marched from Marston Point toward downtown to place the crosses on the steps of City Hall.

1988

New Lambda Pride didn’t last and another ad hoc group, “ParadeFest” got together to put on the weekend. They had 15,000 spectators for the parade with 90 contingents and the Grand marshals were Judy Forman (a gay community advocate and owner of The Big Kitchen restaurant) and Clint Johnson (owner of Show Biz Supper Club and Bee Jay’s, and founding board member of the AIDS Assistance Fund of San Diego County).

Helen Reddy headlined the festival at Old Balboa Naval Hospital parking lot at Park Boulevard and Presidents’ Way. Doug Moore said she was paid $5,000 and was supposed to have a band, but showed up alone with a tape recorder. The two-acre Balboa Hospital parking lot was larger than WCPC’s lots and allowed for carnival rides, a beer garden, multiple dance floors (including country-western), a children’s area, and a resource fair.

After the weekend was over, the board was still in $40k debt and disbanded again.

1989

San Diego Lesbian and Gay Men’s Pride Alliance formed anew with Tim Williams as the first executive director (according to Doug Moore, San Diego was the first Pride organization in the country to have an ED.)

Held June 8-9, attendance and participation decreased but the organization was able to pay off past debts and save for the future year.

Grand marshals were longtime San Diego activists Jeri Dilno and Jess Jessop (Jessop died the following year due to complications of AIDS).

The festival was held for two days at the Balboa Hospital parking lot.

1990

The weekend consisted of the Front Runners Pride Run, parade, rally, and a two-day festival. The theme “Look to the Future: A New Decade of Pride” was selected to emphasize the continued fight for equality moving forward. While the rain almost canceled the parade, it stopped an hour prior, just in time for the 80 contingents and 13,000 spectators to see two black members of the community as grand marshals for the first time ever: Cynthia Lawrence-Wallace and Fundi.

After the rains poured down on the parade that year, it was decided the parade would no longer be held in June, but late July.

1991

Barbara Blake took over for Tim Williams as executive director, after he had been diagnosed as HIV positive. Maryanne Travaglione served as co-director. The theme was bilingual for the first time, “Together In Pride, Conjunto En Orgullo.” The San Diego Sheriff’s Department had a recruitment booth at the festival.

1992

Pride saw increased representation of law enforcement and political officials. San Diego Chief of Police Bob Burgreen was awarded the new honorary title “Friend of the Year.” He rode in the parade, which took place on July 18, along with Mayor Maureen O’Connor and Councilman John Hartley, leading a contingent of city employees. Burgreen was the first Chief of Police to participate in Pride, and this contingent formed the largest delegation of elected officials in a San Diego Pride parade to date.

1993

This year’s parade, on July 17, began at University Avenue and Normal Street and ran through Hillcrest along University to conclude at Robinson and Sixth avenues. For the first time, the San Diego Unified School District had its own contingent in the parade. The new Chief of Police, Jerry Sanders, also participated. Several contingents from Tijuana joined the parade, including Grupo Y Que, which featured gay men wearing traditional folklórico dresses. The festival was moved to Marston Point, where it is still held today.

1994

Despite former (and ousted) mayor Roger Hedgecock’s full tilt to the right with a crusade to end San Diego Pride (bolstered by his radio show), the community still had some cause for celebration. A week before Pride, a San Diego Superior Court judge ruled in favor of police officer Chuck Merino who had been ousted from a Boy Scouts Explorer post for being gay. On July 9, 300 lesbians marched down University Avenue in a Dyke March organized by the Lesbian Avengers.

That same year, the organization received 501(c)(3) nonprofit status and underwent some identity changes. Although still officially called “Lesbian and Gay Pride,” the weekend of July 15-17, 1994, was described as “a celebration of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgendered people” in the souvenir program. Additionally, the event saw an increase in corporate Pride sponsors, including Motorola, 92.5 “The Flash,” and Starbucks Coffee. The annual rally was newly named “the Spirit of Stonewall Rally.”

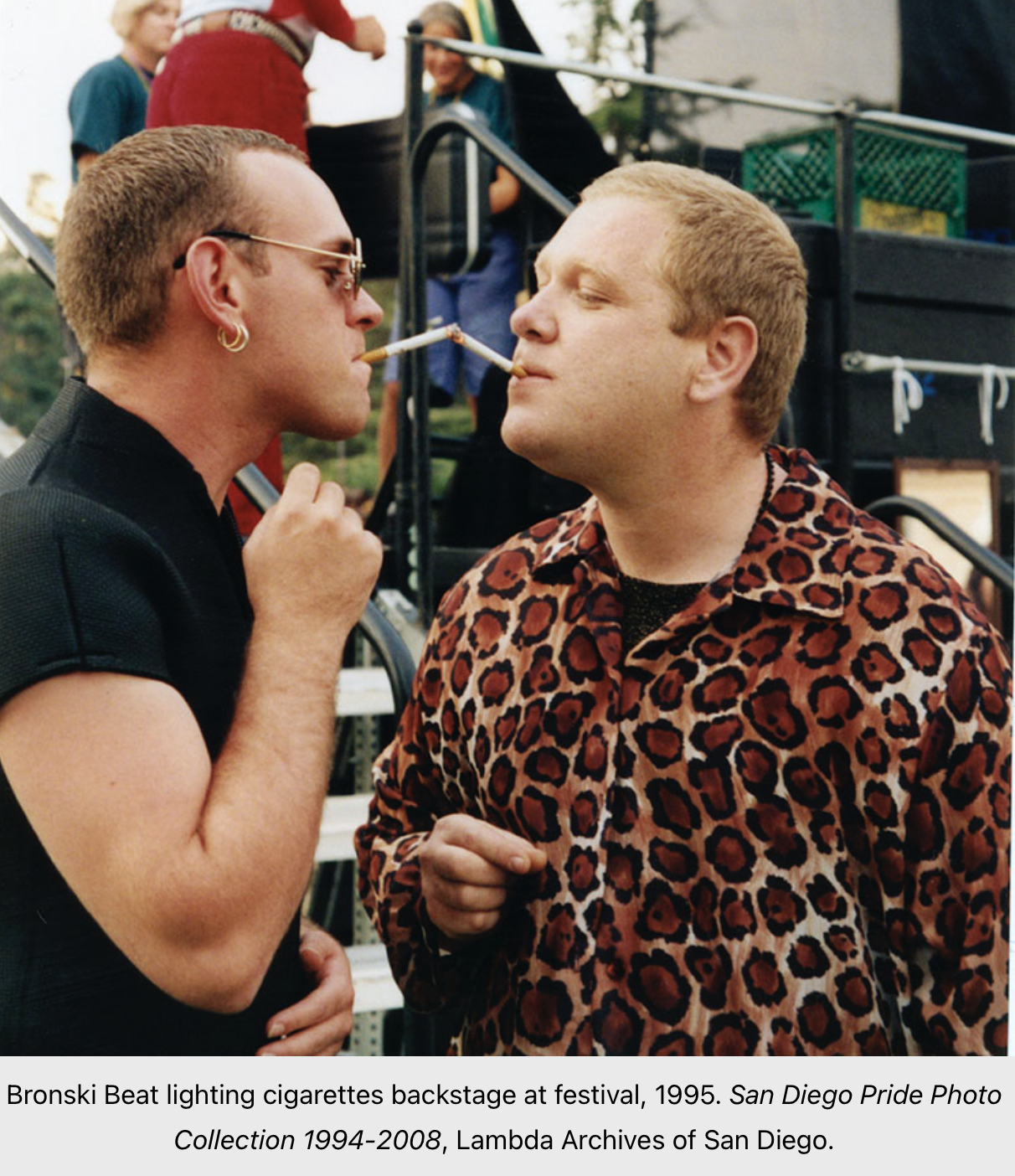

1995

The Pride theme “Out & Free” was selected to highlight the importance of coming out. Greg Louganis, four-time gold medalist Olympic diver, was honored as grand marshal. Louganis, originally from El Cajon, came out the previous year as gay and HIV positive. Louganis was the first internationally-known figure to be selected as a grand marshal, which undoubtedly contributed to the large turnout at that year’s Pride.

1996

San Diego Pride focused on politics, as a presidential election was set for November. The Republican National Convention was scheduled to take place in San Diego from Aug. 12-15 and the GOP at large held an anti-gay position. San Diego Pride launched a “Rainbow Flag Campaign” to encourage widespread display of rainbow flags demonstrating San Diego’s strong gay presence to RNC attendees. Additionally, Pride weekend was pushed back to the end of the month (July 26-28) to lead into the convention.

1997

Former Pride Festival Coordinator Mandy Schultz was named executive director after Brenda Schumacher stepped down to pursue new challenges.

In the weeks leading up to Pride, national and international media swarmed into town due to serial killer Andrew Cunanan’s connection to San Diego. Cunanan, a San Diego native, went on a cross-country killing spree which began with the killing of his friend Jeffrey Trail on April 27, and ended with the murder of fashion designer Gianni Versace on July 15, ten days before San Diego Pride. Rumors swirled around the community that Cunanan might return to San Diego in time for Pride. The possibility of a return was serious enough for a swarm of media and law enforcement to descend on Hillcrest.

1998

Transgender activist Leslie Feinberg was the keynote speaker at the Pride rally, marking the first time a transgender person was spotlighted at San Diego Pride in this way.

1999

The parade started at noon and was well underway when a tear gas bomb was thrown into the crowd near 10th and University avenues, as the Family Matters contingent was passing by. Chaos ensued as people rushed to get away from the danger, while others ran to the aid of victims incapacitated by the chemicals. The parade resumed approximately 25 minutes later.

2000

Although the LGBT community suffered a defeat when the Knight Proposition (Prop 22) was passed, San Diego Pride held a commitment ceremony on Sunday afternoon at the festival. Couples could express their love and commitment to each other in a ceremony officiated by Rev. Tony Freeman of Metropolitan Community Church (MCC) of San Diego.

2001

To show its commitment to diversity, San Diego Pride printed the annual Pride program guide in both English and Spanish.

2002

San Diego Lesbian and Gay Pride made its last name change to date, becoming San Diego LGBT Pride. The change, considered by many to be long overdue, recognized the diversity within the community.

2003

The parade had grown so large that its start time was moved up to 11 am.

2004

San Diego Pride celebrated its 30th anniversary. The festival expanded north almost to Laurel Street in order to acquire more room for the growing crowds.

2005

One of the biggest crises in San Diego Pride’s history took place in 2005 when anti-gay/ex-gay crusader James Hartline released to the press that his research had indicated that two of the volunteers for Pride were registered sex offenders. The revelation kick-started a series that engulfed the community and threatened the very foundation of the Pride organization. Certain members of the press vilified the Pride board and staff over these revelations, not only for the decision to allow the people in question to remain with Pride, but for not performing criminal background checks on all staff and volunteers in the first place. This is despite the fact that background checks were not common practice among any of the community organizations at the time.

The Pride events went on as scheduled with record numbers of people attending. Afterward, a town hall was organized at The Center by members of the community who were calling for a clean sweep of the Pride organization. Things turned ugly as the moderator lost control of the conversation, but Update! newspaper later estimated that 80 percent of those present supported Pride’s actions and behavior. In the end, the scrutiny and criticism from vocal members of the community had a big effect on the Pride organization, which was run by an unpaid board, numerous volunteers, and a few staff members. Executive director Suanne Pauley, many members of the board of directors, and a number of staff and volunteers resigned.

2006

Ron DeHarte takes over as executive director of the San Diego Pride organization. On Saturday night, three young men went on a gay bashing rampage near the festival grounds. Six men were attacked by the three using baseball bats. One of the victims, after his attackers moved on to other targets, called 911 on his cell phone and followed his attackers before stopping to give aid to another one of the victims. These events led to several community conversations and meetings about safety, and was the impetus for the creation of the Stonewall Citizens Patrol, which remained in operation until 2020.

2007

San Diego Pride added a new category to its annual Spirit of Stonewall Awards – the Inspirational Couple. This paid homage to long-time couples within the community, and the first honorees were Cynthia Lawrence and Peggy Heathers, a couple of over 35 years, and Jerry Peterson and Dr. Bob Smith, a couple of 40 years. The category has been renamed in recent years to “Inspirational Relationship” to broaden its scope and include different sorts of personal relationships that exist in the community.

2008

Marriage equality was front and center at this year’s Pride events as Proposition 8 was on the November ballot. Kathy Griffin headlined the festival attracting one of the largest crowds to date.

2009

The 40th anniversary of the Stonewall Riots was celebrated throughout the parade.

2010

The San Diego Pride organization was once again ousted by the community, requiring a team of former leaders to take over and produce a successful Pride celebration. Online media San Diego Gay & Lesbian News had released a scathing investigative report accusing the president of the board, Dr. Phillip Princetta, of “dipping into the til” to his own benefit. Executive Director Ron DeHart resigned over the news and moved to Palm Springs, where he has overseen an incredibly successful Pride celebration each November in the decade and a half since.

2011

Attendee Will Walters was arrested on the festival grounds (for indecency) by the San Diego Police Department for wearing a leather gladiator outfit that didn’t fully cover his buttocks. Walters sued the police for anti-gay discrimination but a federal jury ruled against him. He died by suicide in 2016.

2012

San Diego Pride celebrated the repeal of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” with the first active-duty military contingent marching in uniform, thus capturing the local, national and global media spotlight.

2013

Stephen Whitburn takes over as general manager of the Pride organization.

2014

Stephen Whitburn is promoted to executive director.

2015

Despite the rain, our community remained strong and made the best of the situation by dancing, cheering and celebrating many milestones, including Pride naming the transgender community as the grand marshal. Republican Mayor Kevin Faulconer and his wife Katherine marched the entire parade in the rain. Despite the downpours, thousands showed up Saturday night for Ruby Rose’s DJ stint at the main stage.

2016

Following the 2016 Pride celebration, the board of directors terminated then-executive director Stephen Whitburn. The board did not share any reason for Whitburn’s termination with the community, although one board member shared with local media that Pride “wanted to go in a different direction.” Dozens of community members rallied in support of Whitburn, who filed a wrongful termination lawsuit against the organization in 2018. Whitburn was elected to the City Council representing San Diego’s District Three in 2020, and is currently running for a second term.

2017

After a long search and vetting process, Eric Heinritz, an applicant from the Midwest, was selected as the new executive director weeks before Pride weekend. He resigned six months later.

2018

Fernando Z. Lopez became executive director of San Diego Pride, after working for the organization since 2011. They were the first Latinx and first nonbinary leader of the organization.

2019

To accommodate the even larger number of parade contingents, the parade start time was moved up to 10 a.m. and San Diego Pride became the first Pride in the world to have a military jet formation fly over the parade route.

2020 – 2021

Due to COVID-19, the 2020 and 2021 parades were moved from an in-person live event to an online virtual parade.

2022

The Pride Parade was back, and San Diego Pride was the first Pride in the continental United States to welcome the Marine Corps Marching Band to the pride parade.

2023

Lopez abruptly left the organization in November 2023 with the board of directors giving no reasoning behind their departure in a series of town hall meetings to discuss San Diego Pride’s future.

2024

Pride staffers Jen LaBarbera and Sarafina Scapicchio were named interim co-executive directors and are currently serving in those roles until the board completes its search for the organization’s next leader.

This year, San Diego Pride will celebrate 50 years since the first march in San Diego. For the first time ever, the San Diego Pride Parade will be aired on TV, as CBS8 will broadcast it live on their affiliate The CW San Diego from 10 am to 2 pm.

*This article has been updated with information for 2001, 2002, and 2007

Important message from our publisher.

Greetings,

My name is Eddie Reynoso and I am the publisher of LGBTQ San Diego County News. I am also the voice behind GlitterBot, our AI augmented voice narrator which you can listen to in the majority of our articles. I hope you found this article relevant to your life.

LGBTQ San Diego County News is one of California’s last LGBTQ print and online news sources, and one of a dwindling number of LGBTQ news sources in the nation. But we need our readers’ support to keep it going. Please consider making a donation to our newspaper. Even something as small as $2 a month will help keep us sustainable.

There are other ways you can help; donate, subscribe, or advertise with us to help our dedicated journalists continue providing crucial information that is relevant to your life.

Help us tell the spectrum of stories that are all too often ignored by mainstream media. Help us elevate the spectrum of LGBTQ voices within our community. Help us tell the spectrum of stories that matter to our LGBTQ community. Help us tell stories written by our community, for our community, before they are told by someone else.

Please do whatever you can today so we don’t lose out on this vital community resource. Giving as little as $2 a month will help us stay in print. Click the red donate button to give now. With your support, together, we can ensure our community’s needs are met for years to come! I and our team appreciate your support.

Sincerely,

Wonderful history. However there is one mistake: 1996 – only the festival was canceled due to lack of funds. I was away at a Regional Pride meeting when the vote was taken.

The group that David Manley formed only put on the festival and if my memory is still good there was a lot of discussion afterwards about who was going to produce the ’97 event. They decided to rejoin the Pride board and help produce the next year’s event.

As Always

Yours in Pride

Doug Moore

SD Pride Emirates

Thank you for this correction!